YES VIRGINIA, THE UNITARIANS HAVE MYSTICS-TWO TRANSCENDENTALISTS (PART I)

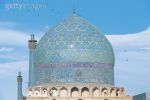

OK, OK, Unitarians do not have (to my knowledge anyway) ardent pious folk who took the path of asceticism to the degree of wearing a hair shirt or living in a desert cave for decades. For edification’s sake, asceticism is the part of the mystic or saint’s path that includes renouncing worldly pleasures in order to become closer to God. Those who have taken these extreme measures did seem to have some remarkable “other worldly” spiritual experiences (see Teresa of Avila, Francis of Assisi, Rabi’a of Persia, and lots of others in almost every other faith, including Buddhists and Hindus (Gandhi chose a life of asceticism as well). So, I am not knocking it. It just that most people do not feel such a calling.

OK, OK, Unitarians do not have (to my knowledge anyway) ardent pious folk who took the path of asceticism to the degree of wearing a hair shirt or living in a desert cave for decades. For edification’s sake, asceticism is the part of the mystic or saint’s path that includes renouncing worldly pleasures in order to become closer to God. Those who have taken these extreme measures did seem to have some remarkable “other worldly” spiritual experiences (see Teresa of Avila, Francis of Assisi, Rabi’a of Persia, and lots of others in almost every other faith, including Buddhists and Hindus (Gandhi chose a life of asceticism as well). So, I am not knocking it. It just that most people do not feel such a calling.

In fact, most people are adverse to giving up anything they find pleasurable, even when they know it is bad for them (hence the challenges during Lent…) However, no matter how we may kick and scream, there must be some giving up of comfort, security, and ego, in order to attain any real semblance of Communion (with a capital C).

The first and most famous of the Unitarian “mystics”, who chose a counter cultural lifestyle of purposeful simplicity that reflected and embodied both an ancient and more modern approach for those seeking unity with God, with Nature, and others, was Henry David Thoreau. Coming from a family of wealth and privilege, with a Harvard education, Thoreau (much maligned in his day for it…he was considered eccentric by the kindest and a nut by the rest) chose to live in a hut in the woods of Concord, MA for two years to isolate himself from society so that he could better understand himself and others. His classic book, Walden, or, Life in the Woods, now required reading for most High School students, is a compilation of this experiment. Unlike the Desert Fathers, he was not intending to live as a hermit, and did take visitors, he was instead seeking to understand life more deeply by consciously removing many of its distractions.

The first and most famous of the Unitarian “mystics”, who chose a counter cultural lifestyle of purposeful simplicity that reflected and embodied both an ancient and more modern approach for those seeking unity with God, with Nature, and others, was Henry David Thoreau. Coming from a family of wealth and privilege, with a Harvard education, Thoreau (much maligned in his day for it…he was considered eccentric by the kindest and a nut by the rest) chose to live in a hut in the woods of Concord, MA for two years to isolate himself from society so that he could better understand himself and others. His classic book, Walden, or, Life in the Woods, now required reading for most High School students, is a compilation of this experiment. Unlike the Desert Fathers, he was not intending to live as a hermit, and did take visitors, he was instead seeking to understand life more deeply by consciously removing many of its distractions.

What Thoreau was emphasizing (among other themes) was the necessity of solitude, contemplation, and nature to “transcend” our over hurried existence. His words and works still call to us today, timeless in their appeal: “As you simplify your life, the laws of the universe will become simpler, solitude will not be solitude…nor weakness weakness.” While many of his oft quoted words ring of the uniquely American self-reliant spirit, they too challenge us to think and be, rather than to be always about the business of doing. For as Thoreau puts it, “Being is the great explainer.”

Many of his criticisms of society were harsh and at many times his views are expressed in an overly zealous manner. Is that not true of the prophets, the social reformers, and those considered holy men and women of every place and time? I am not suggesting by this question that Thoreau was unique or special as a long revered saint, he was a man with his foibles and misinformation. Yet there is a reason we keep reading him.

Many of his criticisms of society were harsh and at many times his views are expressed in an overly zealous manner. Is that not true of the prophets, the social reformers, and those considered holy men and women of every place and time? I am not suggesting by this question that Thoreau was unique or special as a long revered saint, he was a man with his foibles and misinformation. Yet there is a reason we keep reading him.

Thoreau is not asking us to build ourselves a cabin and live in the forest, he is asking that we shake off our complacency, that we do not live an unquestioned and unreflected life. If we are happy with our lives, that’s good and yet we should challenge our assumptions and think more broadly. If we are unhappy, he is pointing to another way.

“If a man (or woman :)) does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”